Many people helped bring this study to fruition. First, we

want to express our appreciation to several people at Tabor College for their

help with this project. President David Janzen reviewed the prospectus and

encouraged us to undertake the study. Executive Vice President of Academics and

Compliance, Frank Johnson, wrote a letter of introduction and support to the

Class of ’67. Vice President of Philanthropy, Ron Braun, and Rod Hamm,

Director of Alumni Relations, helped us track down classmates and cross-check

email addresses. Jim Paulus, Assistant professor of Psychology and Chair of the

Tabor Institutional Review Board, facilitated the review and approval of the

research methodology and questionnaire by that group. Thank you all so much!

We also want to thank several faculty colleagues from other

universities who reviewed the survey instrument and suggested changes that

improved it: Duane Stoltzfus (Communications; Goshen College), Lindsey Ibanez

(Sociology; Washburn University), Doug Penner (Former President; Bethel

College, KS), Mike Yoder (Sociology; Northwestern College, IA), and Norm Ewert

(Economics; Wheaton College, IL). Their comments and suggestions helped us

sharpen the questions and refine the instrument.

We asked several people who graduated from Tabor just before

or after we did to complete the questionnaire as a pre-test and share their

comments, suggestions, and observations with us. Based on the suggestions from

those who took the pre-test, we made a number of modifications. We promised

them anonymity and so we can’t thank them by name here, but we’re

grateful for their help!

Wayne Steffen polished the report and made it more coherent

and readable. Thanks, Wayne! The four of us, however, are responsible for any

errors in the data, analysis, or presentation.

This project would not have been possible without the

understanding, love, and support of Anita, Ginger, Ruth, and Priscilla! Zoom

calls frequently ran late. Lunches were delayed. Other projects and outings

were placed on hold because we were so involved with this study. Thank for your

patience and understanding, as well as for those occasional—and needed—reminders

that our combined male perspective might have missed something!

This report is based on a

research project that grew out of conversations among the four of us who

graduated from Tabor College in 1967. We all worked in Africa, went to graduate

school, and then spent most of our careers in higher education, where

conducting research and publishing the findings became part of our professional

lives. Over the decades, we talked with each other and exchanged emails. We

reflected on our Tabor experience and noted the ways through which it

influenced the trajectory of our lives and professions. We also wondered how

our classmates viewed their college experience 50+ years later and how

attending Tabor affected their lives and careers. We decided to ask them.

We discussed at length who

should be considered a “classmate.” We ended up with a list that

included all who graduated with us in 1967, those who began with us but

graduated from Tabor a year earlier or later than we did, and those who spent

at least two years as “one of us.” We ended up with 50 respondents

out of the 74 living classmates from 1967. As members of this class, the four

of us also completed the questionnaire. See Appendix I for more details about

the methodology used in the study.

Every research project has

certain limitations. So does ours. However, a response rate of 68% is very high

for social science research. There are things we’d do differently next

time but we’re confident that the data generally represent the Class of

’67.

We want to express our deep

thanks to all of you who completed your questionnaires. We hope you will find

the results as interesting as we did! We also hope that what we learned will be

helpful to Tabor College and others interested in Christian higher education.

back to table of contents

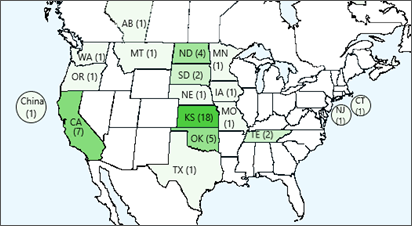

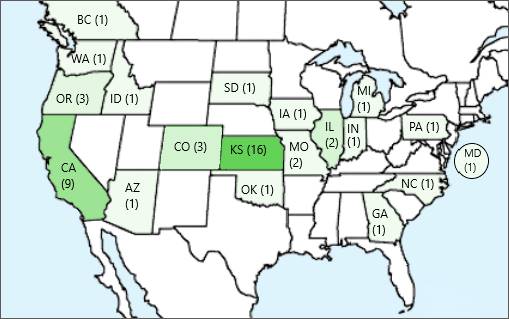

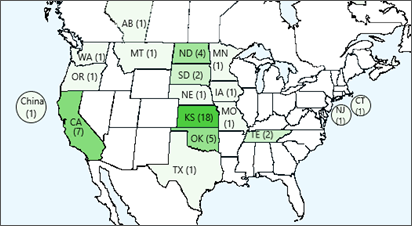

We begin our review of the data

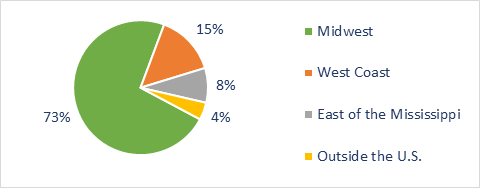

by examining the background characteristics of our class. Figure

1‑1 shows the states or countries in which those who responded to the

survey were born:

Figure

1‑1 The places where members of the Class of '67 were born.

Thirty-five percent of us came

from Kansas, where Tabor College is located.

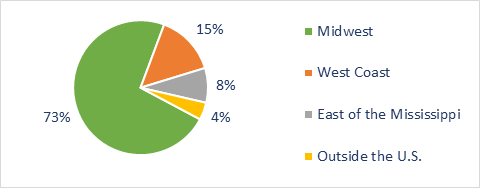

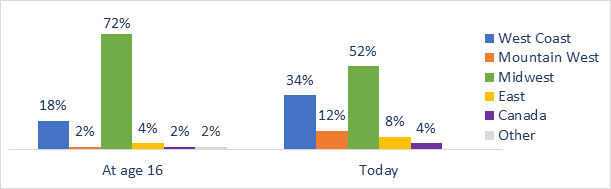

Figure

1‑2 shows that three-quarters came from the Midwest (defined here as the

region between the Mississippi River and the Rockies). Only 4% were born

outside the United States.

Figure 1‑2 The regions from which we came.

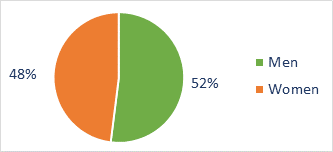

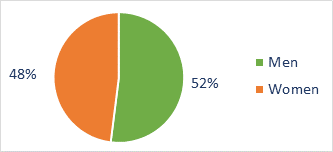

There was nearly an even split

between the number of men and women in our class as Figure 1‑3 shows:

Figure 1‑3 The composition of our class by gender.

Of the 50 respondents in our survey, 26 were men and 24 were

women. That apparent 52%-48% balance contrasts with the fact that nationally,

50 years ago, 58% of college students in the U.S. were men. But the percentages

among our respondents are distorted by a startling reality that affected our

pool of available respondents: over the past half century 26 of our classmates

have died—22 of them men, and four women. A count of pictures in Tabor Bluejay yearbooks

showed that our freshman class had 61 men and 48 women (56% male). Our senior

class had 37 men and 31 women (55%). Both of those figures are closer to the

national average at the time.

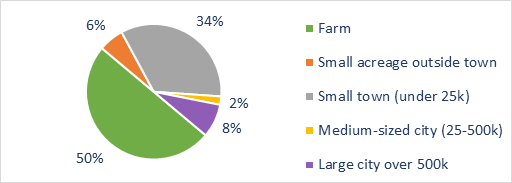

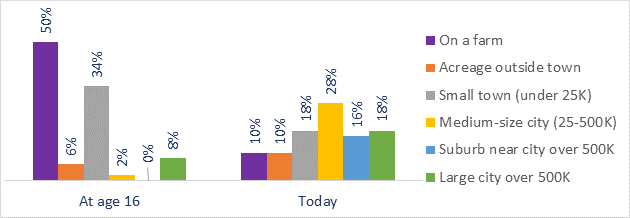

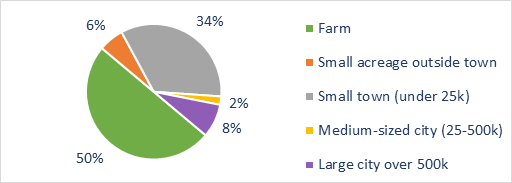

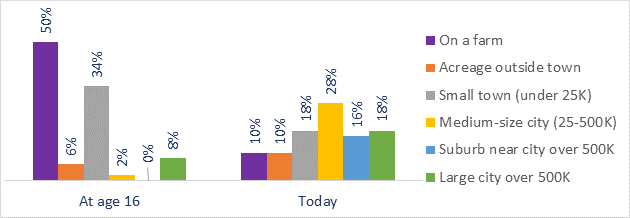

We asked respondents where they

lived at age 16. Figure 1‑4 reflects the small, rural communities from

which we came:

Figure 1‑4 The types of places in which we lived at age 16.

Half of us grew up on farms,

several on small acreages, and another third in small towns. Only a few came

from medium or large cities.

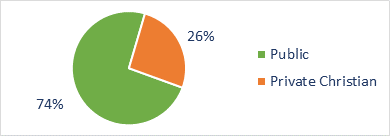

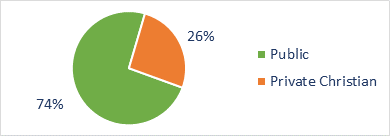

We wanted to know whether our

classmates attended Christian high schools, graduated from public schools, or

were home-schooled. Figure 1‑5 shows what we learned:

Figure 1‑5 The type of high schools from which we graduated.

Three-quarters attended public

high schools, but a significant proportion graduated from private Christian academies.

None reported being home schooled.

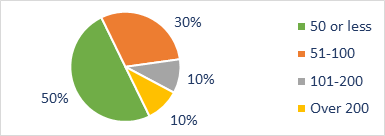

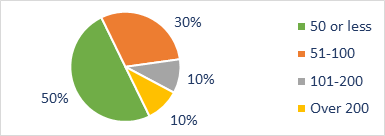

Most of us came from very small

high schools as the following graphic shows:

Figure

1‑6 The number of students in our high school graduating classes.

Only 20% of us were part of

graduating classes larger than 100 students. This reflects the small towns and

rural communities from which we came.

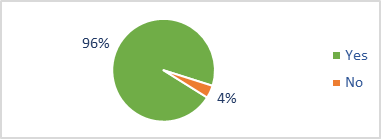

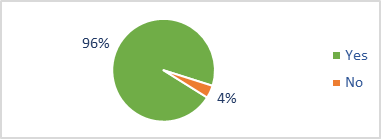

From high school to college

Figure 1‑7 The percentage of us going straight from high school to college.

With nearly all of us going

directly from high school to college, we were clearly young and had little life

experience. Going to Tabor was our first step toward becoming independent

adults.

Tabor College was the U.S.

Mennonite Brethren Church’s only four-year college as we were completing

high school. (Fresno Pacific University, Tabor’s sister school, started

its four-year program in 1963 and was accredited as a four-year college in

1965, a year after Tabor.)

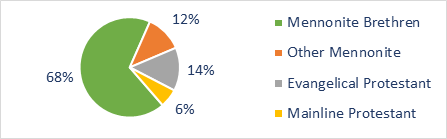

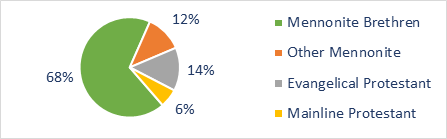

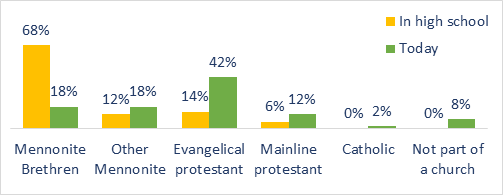

Figure 1‑8 shows that

two-thirds of us grew up in Mennonite Brethren (MB) congregations, increasing

the likelihood that we would enroll at Tabor:

Figure 1‑8 The churches we attended during our

senior year of high school.

No one reported coming from the

other options that we provided: Pentecostal,

Catholic, Not

part of a church… or Other religions.

The majority of us came from Mennonite backgrounds, but we will see later that

our denominational affiliations changed over the years.

back to table of contents

We asked several questions about

the families in which we were raised. We were interested in the educational

levels of our parents as well as how well off we perceived our families to be

as we grew up.

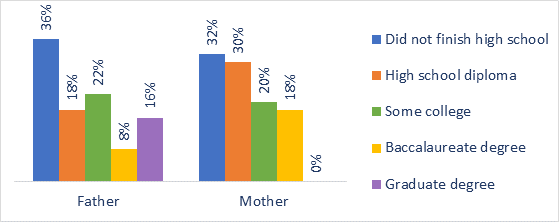

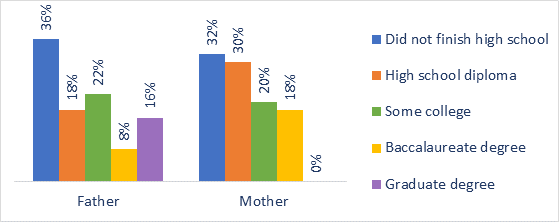

Since the educational level of parents is generally seen as

one factor influencing the education aspirations of their children, we included

this in our study. The distribution is portrayed in Figure

2‑1.

Figure 2‑1 Our parents' education levels.

Around a third of both mothers and fathers did not finish

high school. However, there is a wider distribution of educational levels

among fathers than mothers. Eighteen percent of our mothers earned a

baccalaureate degree, but none of them obtained graduate degrees. A quarter

of our fathers received at least a baccalaureate degree, and more than

half of those fathers went on to earn a graduate degree.

Further investigation showed

that nearly a quarter of us came from homes where neither parent had

finished high school. For 64% of us, neither parent finished college.

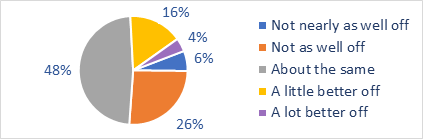

A family’s financial well-being often influences the educational

opportunities of the children. It would be difficult for anyone to objectively

evaluate the actual economic situation of their family five decades later. We

did, however, ask people how they perceived their families’

financial well-being compared to other families in their community as they were

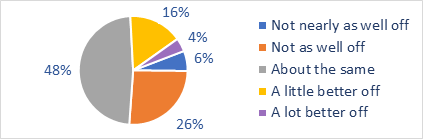

growing up. The results are shown in Figure

2‑2.

Figure 2‑2

How well-off we perceived our families to be compared to other families.

Most of us came from farms or

small towns that tend to be economically more homogeneous than large urban

centers. It’s not surprising that we generally saw our families in the

same economic situation as others in our communities. Forty-eight percent said

their families’ financial situation was “about the same” as

others while only 10% felt their families were a little or a lot better off

than others in their communities. More than a quarter, however, felt their

families were worse off financially than others around them.

The data show that classmates

didn’t have to feel better off than others in their community in order to

go to college. Further analysis showed that the perception of wealth had no

effect on educational achievement.

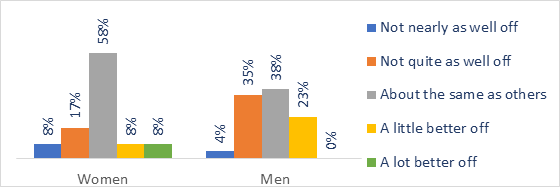

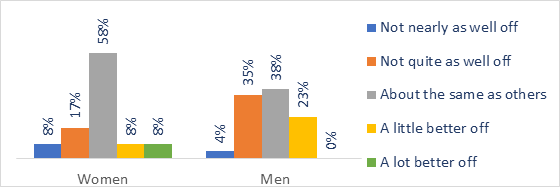

When we compared the perceptions

of men and women about their families’ financial well-being as they were

growing up, we found some minor differences as shown in Figure

2‑3.

Figure 2‑3

Differences in how the men and women perceived their families' financial

well-being.

The majority of women felt their families were financially

the same as others in their communities. Only 38% of the men perceived their

families’ situations as comparable to others, while 39% felt theirs were

less well off than others.

back to table of contents

We noted earlier that nearly all of

us went directly from high school to college. We also wanted to know the

reasons for that decision, why we chose Tabor, and how we experienced Tabor.

We asked our classmates to

explain, in their own words, the reasons for deciding to go to college. The

common theme running through their responses was that their families had

encouraged higher education and created the assumption that college was the

natural, next step after high school. Some of the comments included: "My

parents expected me to go to college." "All my friends

my age were going to college, and my family supported it." "It was

the normal thing to do." This is particularly significant

because more than half of our parents never attended college themselves.

Many saw going to college as "the

key to a good paying job." College would open up career options or

provide a gateway to a particular career. Some saw it as "a way to

escape the farm" or "to stay out of military service."

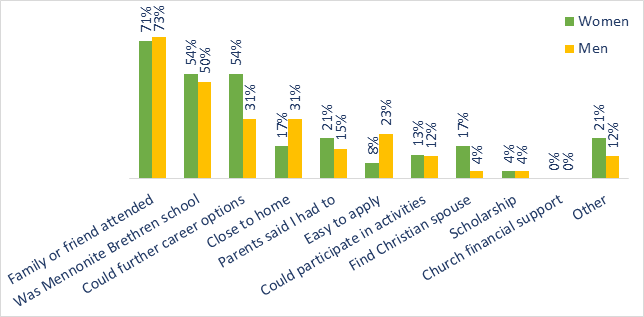

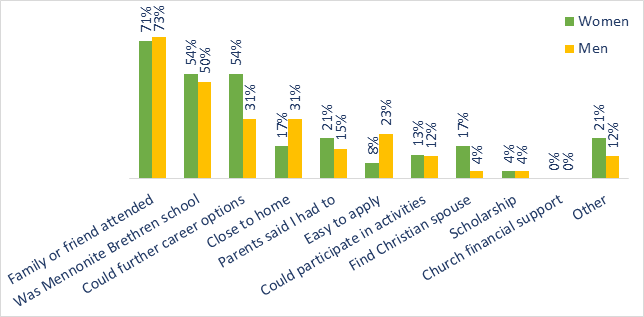

We wanted to know why our classmates chose to attend Tabor,

so based on our experience in higher education, we identified ten possible reasons

for choosing a college. People do things for multiple reasons, so we asked our

classmates to select the three top reasons for having selected Tabor as

their undergraduate institution. In the following chart we compared how men and

women responded to this question:

Figure 3‑1

Our reasons for choosing Tabor. (Each respondent could select up to three.)

Having a family member or

knowing someone who attended was the most significant factor in choosing Tabor.

The college’s affiliation with the MB denomination was the second most

important reason. (Tabor College was the U.S. MB Church’s only four-year

college as we were completing high school in 1963.) The belief that they could

further their career options was also important. The latter, however, was more

important to the women than the men. Proximity to home and ease of applying

were more important to the men than the women.

When given the opportunity to

elaborate on their college choices, several mentioned having grandparents in

Kansas or having previously lived near Hillsboro so they were familiar with the

area. That helped direct them to Tabor. A number noted that there was never

really a question about where they would enroll. They (and usually their

parents) had always assumed they would attend Tabor.

As we will see later, a third of

our classmates did meet their spouses at Tabor. This includes all the

women who indicated that finding a Christian spouse was important.

Several classmates transferred

to Tabor during our junior year after a Christian college in Minnesota that they

had been attending closed. Tabor made it easy for them to enroll.

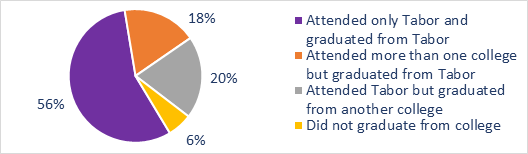

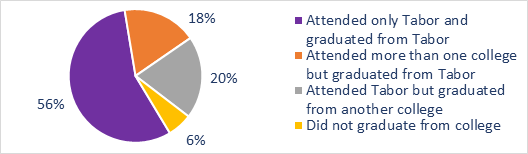

We noted earlier that many in our

class spent four years at Tabor and then graduated. Some attended more than one

college but graduated from Tabor. Others attended Tabor but graduated

elsewhere. Figure 3‑2 shows how much time the Class of ’67 spent at

Tabor.

Figure 3‑2 The amount of time we spent at Tabor.

Three-quarters of the survey respondents ended up graduating

from Tabor, though some had previously attended other colleges. Twenty percent

attended Tabor but transferred out and graduated elsewhere. Several completed

three years of Tabor and then transferred to professional schools such as

dentistry and optometry where they completed their baccalaureate programs

concurrently.

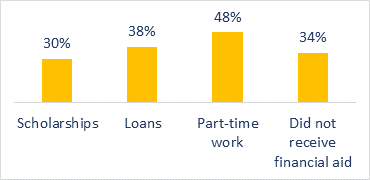

Paying for college today has

become a very significant issue for students and their families. College was a

lot less expensive when we were students. One-third of our class reported that

they did not have scholarships or loans, and were not working part-time during

college, as shown in the following graphic:

Figure 3‑3 Types of financial aid that we

received.

Based on the personal budget

records of one of our classmates, we estimate that when the Class of ’67

were freshmen, Tabor’s tuition for one year cost less than $1,000. By

2021 Tabor’s annual tuition and fees had risen to $32,100. Based on an

online calculator,[1]

the increase in tuition between 1963 and today is three and one-half times the

rate of inflation. This increase is consistent with other higher education

institutions and not unique to Tabor.

In the mid-60s, some students

earned enough on summer harvest crews or other jobs to pay for their entire tuition,

room, board, and fees. That would be virtually impossible today. The National

Defense Student Loan (NDSL) program was signed into law in 1958 but expanded

significantly in the early 60s. This made government loans more plentiful.

Our data show how many of our

classmates took loans through Tabor but not how many families took out private

loans to send their students to college. Loans to families would not

necessarily have been obvious to students. Many of us came from farms that

relied on annual operating loans or lines of credit. Parents may have taken out

operating loans that were also used to cover college costs without students

knowing this had happened.

Though college has become

much more expensive since we were students at Tabor, federal and state

financial aid have become more available. According to the latest data

from the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2020-2021 every Tabor

student received an institutional grant or scholarship. Seventy-three percent

took out federal loans.

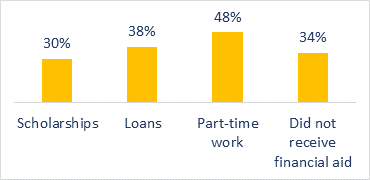

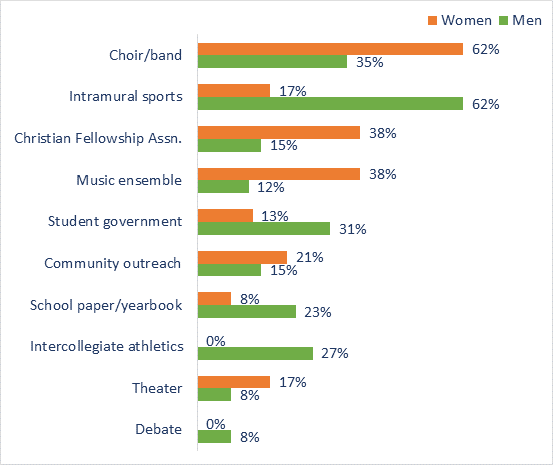

Based on our own experience and the

suggestions of others who reviewed the survey instrument, we identified a

list of those extracurricular activities being offered while we

were students. We asked respondents to note all of those in

which they participated at Tabor. The following figure shows the

percentage of men and women involved in each activity:

Figure 3‑4

Men's and women's participation in campus activities.

Music, intramural athletics, and

Christian Fellowship Association (CFA) were cited most frequently. A higher

percentage of women than men participated in choir/band, CFA, music ensemble,

and theater. More men participated in intramural sports, student government,

the student newspaper and yearbook, debate, and intercollegiate athletics. There

were no intercollegiate sports for women in small Kansas colleges prior to Title

IX, passed in 1972.

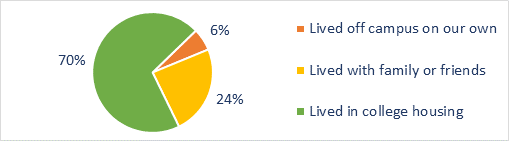

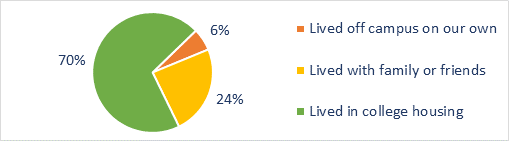

Tabor

was then, and still is, primarily a residential campus. The distribution for

our senior year is shown in Figure 3‑5.

Figure 3‑5 The type of housing in which we lived during our senior year of college.

Most lived in campus housing

while a quarter lived at home, with family, or friends in the community. Several

(generally married couples) lived off campus on their own.

back to table of contents

People go to college expecting

to learn, grow, and change. We asked everyone to comment on how they had

changed at Tabor and the factors involved in that process.

The word

used most frequently to describe how the Tabor experience changed us was "broadening.”

One said, “[It] broadened my view, introducing me to people and ideas

that I had not considered before." Another responded, "I

discovered that there was not just a single correct answer to every question."

A classmate spoke to the broadening theme, saying "It excited and

challenged me to learn that there were so many interesting things to

investigate and consider and that asking questions was a good thing."

Looking back after more than a half-century, the limited

horizons we brought from our mostly rural, small-town childhoods clearly were

expanded at college. For example, one said, "Classmates and others

allowed me to see a broader slice of life and perspectives than I had growing

up in a small rural community." Another noted that college “Started

opening my eyes to a bigger world. It was my first step towards moving into my

own independent life. It also protected me from getting lost on a large

university." In a comparable note, still another suggested that Tabor "gave

me protection because it was small enough for me to adjust to life and not get

lost in the system of life."

Getting acquainted with a wider

range of people was another important part of that "broadening"

experience. As one classmate put it: "I made friends from so many

different places and I began feeling part of the world community." Another

spoke about living in the residence halls: "Dorm living and being

involved with people on a bigger level than my limited exposure of my early

days, really stretched me socially and intellectually." A comment that

reflected what many expressed was, "I developed life-long friendships

through the college although we have become very diversified politically."

Speaking of life-long friends, several emphasized having met their spouses at

Tabor!

Maturing in Christian faith was

another common theme running through what people wrote. As one put it: "[I|

began to think for myself instead of just parroting my parents' beliefs."

Another noted that the Tabor experience "Gave me a deeper understanding

of the faith that I had brought from home and Sunday School and helped shape my

own faith." A classmate said: "[At Tabor] I learned about

Christian service and living a life of humility and service to others."

Some indicated that Tabor

prepared them for specific professions or changed or sharpened their career

focus. The clearest and most common theme running through our

classmates’ comments was that Tabor opened their minds and broadened

their worldviews.

Given

the importance of teaching and mentoring at Tabor, we asked everyone to

identify the person (a professor, staff member, or coach) who influenced them

or was particularly helpful. We followed up by asking what it was about that

person which made the difference in the student’s life.

Respondents listed more than 20

different faculty members or coaches who had been particularly significant in

their lives. Sol Loewen (biology), Delbert Wiens (philosophy), Clarence Hiebert

(Bible and theology), and Clarence Harms (biology) appeared most frequently.

Others named by more than one student were Bill Johnson (chemistry), Roy Just

(sociology and the college president), David Karber (business), Emil Thiessen

(business), Paul Wohlgemuth (choral director), Leonard J Franz (history), Steve

Kimery (coach), Malinda Penner Nickel (English), Vernon Wiebe (dean of students),

and Marvin Kroeker (history).

A classmate wrote: “Delbert

Wiens challenged me to think, to apply my faith, and taught me the principles

of good writing.” Another wrote: “Dr. Paul

Wohlgemuth’s character and Christian testimony through music and example

of serving in the church influenced me.” Someone said: “Dr.

Sol Loewen believed in me and promoted me to leadership beyond what I thought I

could do.” Another said: “Clarence Hiebert provided a

broadened spiritual world view and encouraged me to consider overseas service

in Congo.” Another noted: “Dr. [Bill] Johnson [whose]

enthusiasm and love of chemistry and teaching put a smiley face on the cover of

the chemistry texts I would see during the rest of my education.” A

classmate said: “Ken Kornelsen gave me confidence in myself by telling

me I could succeed in college… [He] believed in me when I didn't believe

in myself.”

Only ten classmates did not

identify someone as having been particularly helpful to them or influential in

their lives.

People’s comments revealed

how highly they valued those who took a personal interest in them or reflected

personal qualities they subsequently tried to model. It was not necessarily the

exceptional teaching in the classroom that made these professors special.

It’s significant that 80% of the respondents could point to a professor

(or professors) who had a specific impact on their lives. This personal

connection was a very important part of our class' collective experience and

suggests that this may have been Tabor’s strongest comparative advantage

over larger and better- resourced institutions.

We asked the Class of ’67 about their theological

perspectives at three different points in time: when they arrived at Tabor,

when they left Tabor, and today. We gave them a five-point scale that went from

Very Conservative to Very Liberal. Figure

4‑1 shows how we changed during

college.

Figure

4‑1 Our theological perspectives on entering and leaving Tabor.

Nearly three-quarters of the

class described themselves theologically as having been either Conservative or Very

Conservative when they arrived at Tabor. Two percent described

themselves as Liberal when they arrived at

college. None described themselves as Very Liberal.

The proportion of the respondents considering themselves conservative or very

conservative dropped to 60% by the time we left Tabor. The Middle-of-the-road group grew as did the

percentage of those who saw themselves as Liberal

when they left Tabor. Again, none described themselves as Very Liberal at that point.

About 40% of our classmates,

using different words, said their theological beliefs had not changed or had

changed very little during their time at Tabor. For those whose theological

perspectives had shifted during college, we gave the opportunity to explain how

this happened, and why.

Among the majority who reported

that their theological perspectives had changed during college, some expressed it

as a deepening faith and moving beyond the “thou-shalt-nots” of

their youth. One described [Going] “… from legalism to

understanding true Christianity." Another: "My commitment to

Christ was reinforced and deepened." One put it this way: "I

became less legalistic and more desiring to live my life by loving Jesus and

wanting to serve Him." The same theme came out in another comment: "I

moved from a legalistic do’s-and-don’ts to an understanding of

Christianity established in the work of Christ."

The "broadening" theme

continued in several other comments: "[I] became more aware of

different perspectives which made me more open to other points of view."

Others expanded on that: "[I] realized that Christians come in all

shapes and sizes." One said: "I no longer believed that only

Mennonite Brethren would populate heaven." The

“broadening” theme came through in another statement: "I began

to understand that the Bible was more than a plug-and-play set of

instructions."

When asked what prompted these changes,

a number of classmates identified Clarence Hiebert's influence. For example: "Exposure

to new ideas, significantly through Clarence Hiebert's World Religions class,

which showed that the majority of the world was not consigned to hell."

Others mentioned the influence of Orlando Wiebe, Clarence Harms, and Delbert

Wiens in reshaping their theological perspectives. A number also noted how

discussions with friends and other students helped shape their new

understandings.

A later section will show how

our theological views have changed since college.

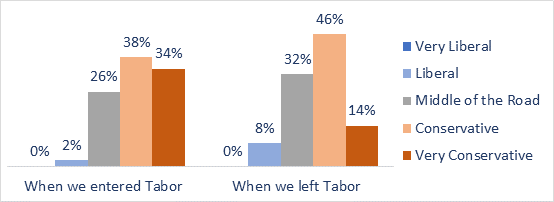

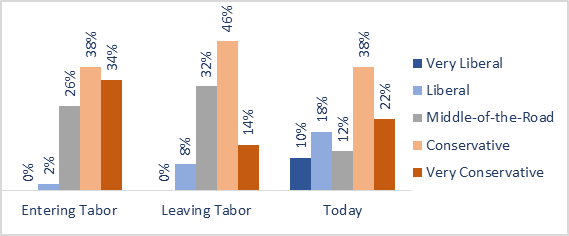

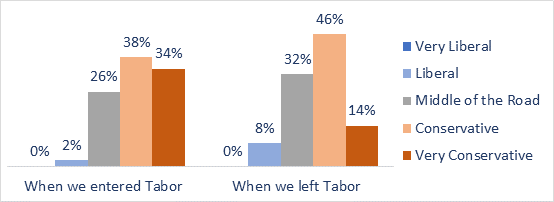

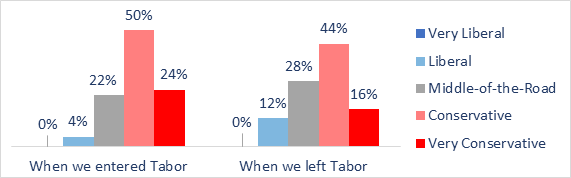

Not only did our theological

orientations shift, but so did the political perspectives of some of our

classmates. Again, we used a five-point scale from Very Liberal to Very

Conservative. Our changes in political perspectives while in college

(Figure 4-2) were less significant than our shifts in theological perspectives.

Figure

4‑2 Our political perspectives on entering and leaving Tabor.

Three-fourths of our class

considered themselves politically Conservative or

Very conservative at the start of our

undergraduate careers. When we left Tabor, the percentage dropped to 60%. Later

in this report, we’ll see that it subsequently dropped further to 50%. Nobody

reported being very liberal either when

they started college or when they left Tabor. The percentage of the class who considered

themselves liberal increased from 4% when

they started college to 12% when they left Tabor.

The data show that our

classmates’ political views changed far less than their theological

views. We found that 70% indicated that their political perspectives did not

change at Tabor. They retained the conservative political orientations that

were formed while growing up in their home communities. We asked those whose political

perspectives had changed during their time at Tabor, what caused those changes?

Many said they had little political interest or awareness during college, as

typified by the following response: "I do not think I changed

politically during college—quite frankly I didn't think much about

it then. I always thought I would hold the same views as my father."

Another said, "I don't recall that political discussion was that much a

part of my experience although I was aware of what was happening in the world."

Of those who acknowledged that

their political perspectives had changed, most indicated they had become slightly

more liberal. The reason? Most in this group reported a growing concern about

the Vietnam War. None, however, hinted at any involvement in anti-war activism.

A few mentioned President Kennedy as an inspirational figure. One person

identified history and political science courses as having demonstrated that "progressive

political, social, and economic programs could make a necessary positive

impact." An individual whose views had not changed admitted that "I

became friends with people who had differing political views and became less

clear that I had the only acceptable perspective." Another classmate

said, "Actually my perspectives changed causing me to become more

conservative."

Clearly, for the Class of ‘67,

Tabor College was not a politically charged place.

back to table of contents

Life

following departure from Tabor presented us with a new set of circumstances. Many

fulfilled their Selective Service obligations, went to graduate school, started

families, or began careers. Many of us lived in multiple states,

some lived abroad, and most traveled outside the country.

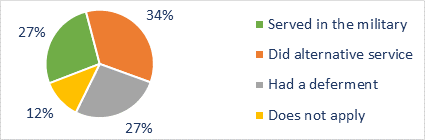

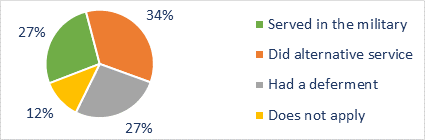

We came of age during the

Vietnam War and military conscription. Consequently, the men who were U.S.

citizens, and therefore subject to the draft, faced a choice on how to respond.

While some received deferments (educational, medical, etc.), the others had to

choose between alternative service or the military. Those choices are

summarized in Figure 5‑1:

Figure 5‑1 How the men in our class fulfilled their Selective Service requirements.

A third performed alternative

service as conscientious objectors. We will see later that many of the latter

served overseas in Africa with the Mennonite Brethren Missions/Services (now called

Multiply) or the Mennonite Central Committee. This was largely attributable to

the active encouragement of Tabor faculty.

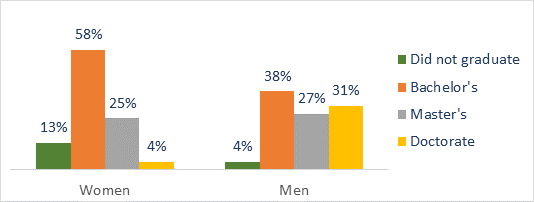

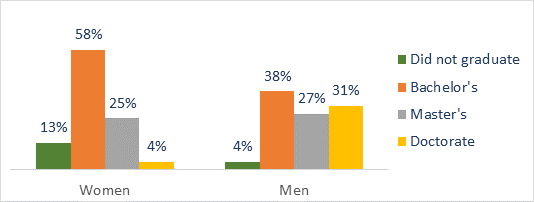

We wanted to know the extent to which our class went on to

earn other degrees after graduating from college and looked at the data by

gender in Figure 5‑2. We collapsed academic (Ph.D.) and professional

doctorates (JD, DMIN, EdD, DDS, and OD) into a single category of doctorates.

Figure

5‑2 Our highest degrees, by gender.

Forty-four

percent of our class went on to professional or graduate school. Similar

percentages of men and women received master's degrees as their highest degree.

However, an additional 31% of men received a doctorate degree, in comparison to

4% of women.

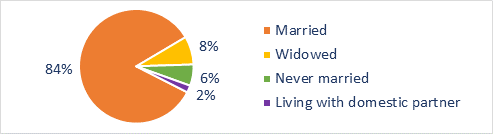

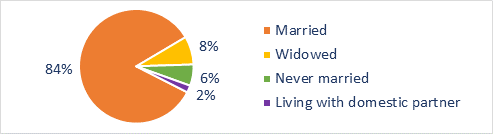

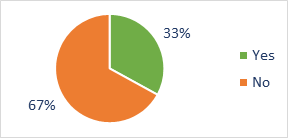

We asked respondents about their

current marital status. (We did not ask about divorce or remarriage.)

Overwhelmingly we are married today (see Figure 5‑3).

Figure 5‑3 Marital status today.

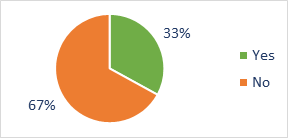

How many of our classmates met

their spouses at Tabor? A college like Tabor would have been considered a

particularly good place for young Mennonites to find a life partner. Of those

who married, one-third of us did.

Figure 5‑4 Meeting a spouse at Tabor.

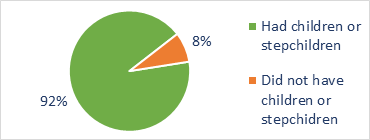

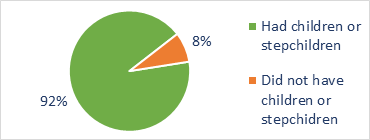

Most of us (Figure

5‑5) had children or stepchildren.

Figure 5‑5 Percentage of the class with children

or stepchildren.

Although many of us were

parents, we will see later that few of our children went to Tabor.

back to table of contents

Americans

have generally become more mobile in recent decades so we asked our classmates about

where they had lived and traveled.

We noted earlier that more

than two-thirds of us came from farms and small rural communities.

Figure 6‑1 shows that

after college, many of us moved to urban centers.

Figure

6‑1 Type of place where we lived at age 16 and where we live today.

Today, 62% of us live in cities

with populations over 25,000. Just over one-third still live on farms or in

small rural communities like the ones from which we came. A third of us live in

large cities or suburbs.

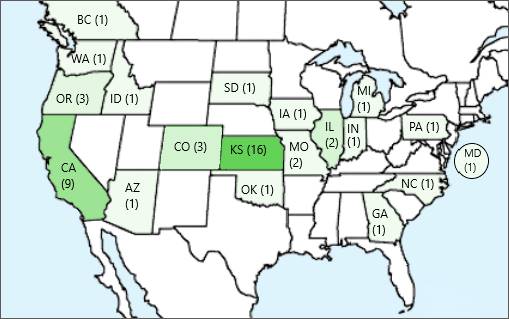

We also broke it down by state (Figure 6-2). As before college, Kansas remains

home to more of our classmates today than any other state, with California a

distant second.

Figure 6‑2 The states and province where we live today.

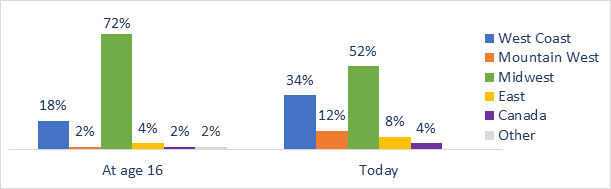

Our class has been mobile. As Figure

6-3 shows, the distribution of the regions in which we live changed markedly after

age 16.

Figure 6‑3 Regions where we live now compared to age 16.

At age 16, nearly three-fourths

of us were living in the Midwest (between the Rockies and the Mississippi), a

figure that dropped to around half at the time of the survey. The percentage of

our classmates on the West Coast nearly doubled (increased from 18% to 34%)

between high school and today.

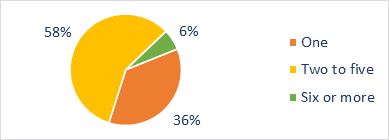

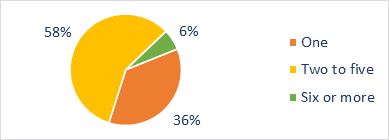

The majority of us (Figure 6-4)

lived in multiple states and provinces over the course of our adult lives.

Figure 6‑4 Number of different states or

provinces in which we lived.

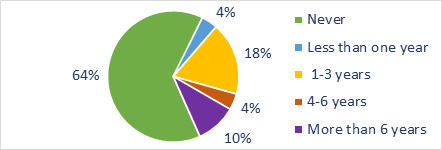

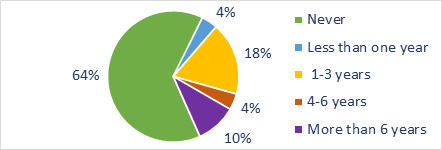

About a third of our class (see Figure

6‑5) lived outside the U.S. or Canada at some point in their lives.

Figure 6‑5 The number of years lived outside the U.S. and Canada.

A number in our class fulfilled

their military or alternative service abroad, which helps account for the

number who lived internationally. Anecdotally, we know that those who lived

overseas for more than six years were serving with the Mennonite Central

Committee (MCC) or other NGOs.

Although Mexico is located in

North America and contiguous to the U.S., we included it as living or traveling

abroad since it would have been an intercultural experience. We did not consider

Canada as being abroad since the two countries share a common language,

culture, a permeable border, and often ties of kinship.

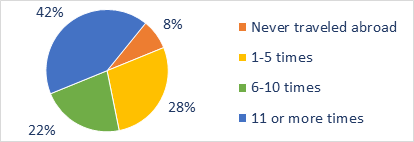

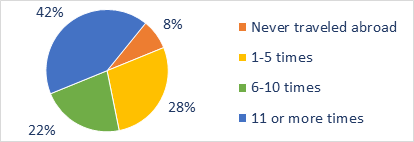

Because we were interested in our

classmates’ intercultural experiences, we asked them about their travels

outside the U.S. and Canada. We found (Figure 6-6) that many of us had

done so.

Figure 6‑6 The number of times we traveled outside

the U.S. and Canada.

Again, this means that many of

our classmates had multiple opportunities to experience other countries and

cultures, though our data don’t show how many of these trips involved

cruises or vacations in the Caribbean.

back to table of contents

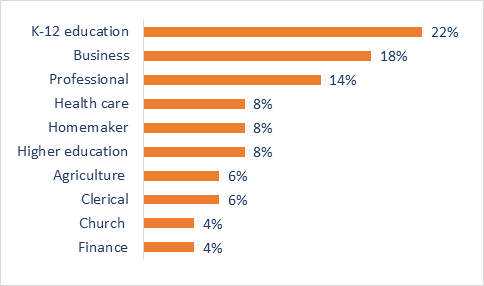

We were interested in our

classmates’ professional lives and careers after Tabor, so we asked them

what they did. We also asked them how they felt about their lives’ work.

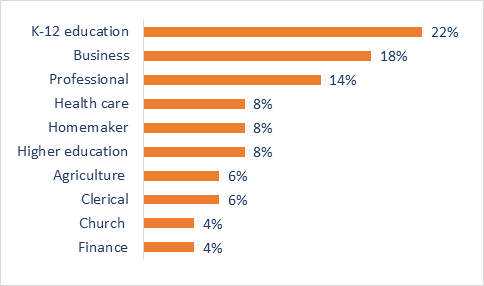

Rather than try to create an

exhaustive list of potential careers in which our classmates had been involved,

we asked an open-ended question about their primary occupations. We then

clustered their responses into the occupational categories presented in Figure

7‑1:

Figure 7‑1 Our primary occupations.

Education was the largest occupational field. Together, K-12

education and higher education employed nearly a third of our classmates. Business

and the professions were the next largest groups. Under business, we included

small business owners (photography studio, quilt shop, print shop, travel

agent, business products) and business managers. Professional included

accounting, journalism, fishery scientist, library science, and human resources.

Medical included medical research, nursing, dentistry, and optometry. Finance

included banking and financial services. The respondents in the church

category were pastors.

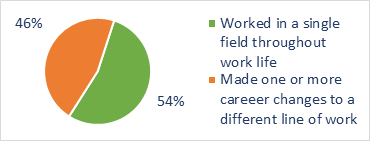

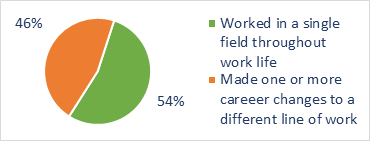

We were interested in the extent

to which people remained in the same field throughout their careers or switched

occupations at some point. Figure 7‑2 shows what we learned:

Figure 7‑2 Working in a single field versus changing to a different line of work?

Slightly more than half of the

respondents indicated that they had spent their entire careers in a single

field while the others reported making one or more career changes. To be clear,

we specifically asked about career changes rather than job changes

since most people hold multiple positions over time, often with increasing

levels of responsibility.

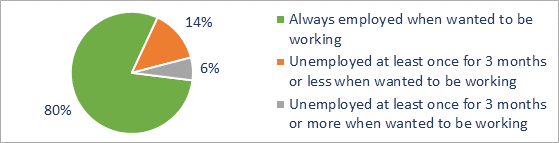

Because we have lived through

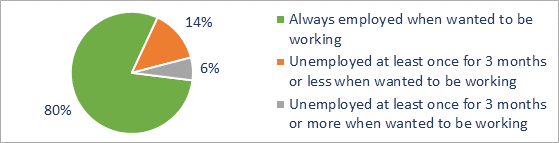

periods of heightened unemployment during our adult lives, we asked about the

extent to which our classmates were employed when they wanted to be working. The

level of unemployment in our class (Figure 7-3) over the 50-year period was remarkably

low.

Figure 7‑3 Unemployment when we wanted to be working.

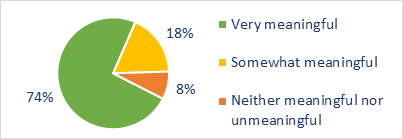

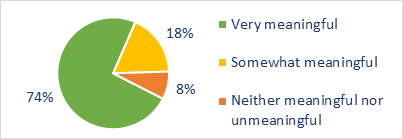

We then asked our classmates to

reflect on how they now see their lives and careers. Specifically, we asked

them to indicate how meaningful they found their work using a five-point scale

ranging from Lacked Meaning to Very meaningful.

Figure 7‑4 The extent to which we found meaning in our life's work.

Ninety-two percent of our class

see their life’s work as Very meaningful

or Somewhat

meaningful. No one suggested they saw

their life’s work as having Lacked meaning.

Clearly, those in the Class of ’67 feel good about their life’s

work and careers.

When given the opportunity to

elaborate further, our classmates spoke almost in unison about what they meant

by “meaningful.” However, no one defined meaningful as “importance.”

Nor did anyone mention accomplishments, fame, or fortune. Was that because no

one climbed high up the corporate ladders or achieved enormous wealth? Or

because our parents, churches, home communities, and college education infused

us with a different definition of meaningfulness?

“Making a difference in

the lives of others”–whether students, customers, clients,

co-workers–was a common phrase people used to describe what made their work

meaningful. Several variations of the theme included: “I enjoyed

working with people and finding ways to make their lives more enjoyable and

meaningful.” Or “Teaching children to read [and] write, I

think was a very positive experience for me.” Or “People

should see God through you.” Or “I believe what I did made a

difference to my students and to the organizations in which I served.”

Several took satisfaction and

inspiration from meeting challenges. One said, “It was challenging,

served our customers often in social and emotional ways…it fed my

creative gifts.” Another said that “What I did from day to

day was intellectually challenging and satisfying.” One noted

satisfaction in that “I was always learning and continually facing new

challenges.”

Those who rated their work more

neutrally—neither meaningful nor unmeaningful—described it in more

guarded terms: “My occupation as a teacher was not particularly

meaningful. It was the way I earned a living. I was a good teacher, but not a

gifted teacher. It turned out well. I have no regrets.” Others said,

“Sometimes [my occupation] seems so vain, but it fulfilled a purpose for

my community.” One called it “…a job. Brought in income

and benefits.” Similarly, there was a comment that “[it] provided

for my family, and set my stage for retirement.”

back to table of contents

As Tabor graduates, we wanted to

know how closely, and in what ways, our classmates had stayed connected with

the college. Did they send their children to Tabor? Did they attend Tabor

events? Donate money? How do they feel about their Tabor experience five

decades later?

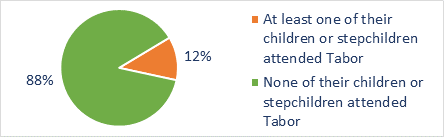

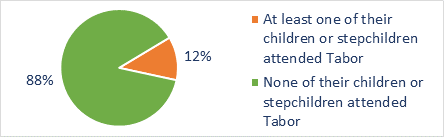

Although 92% of us had children,

few of them (Figure 8-1) followed us to Tabor.

Figure 8‑1 The percent whose children or stepchildren attended Tabor.

It would be interesting to explore

why so many who attended Tabor had a good experience and graduated there, but their

children went to other colleges.

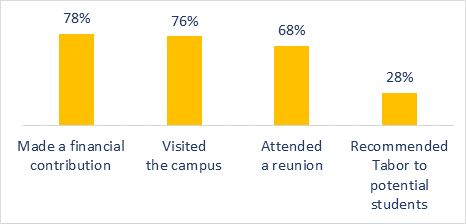

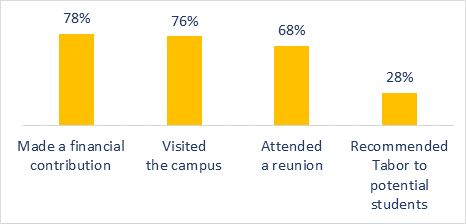

We also asked about the ways in

which they have interacted with Tabor since graduation. We provided several

options (Figure 8‑2).

Figure 8‑2 Our interaction with Tabor since graduation.

Our classmates are arguably

better connected with each other than are those in other classes. For example,

the class organized a 50-year reunion and followed it with a two-day retreat in

Hesston that brought together more than 35 people. In conjunction with the Golden

Graduate celebration at Tabor, the Class of '67 raised $30,000, which was a

record class gift.

Although not part of the

questionnaire, we are unaware of any of our classmates serving on the Tabor

faculty or the Board of Trustees.

While many contributed

financially to the college, our data show that only a quarter of the class had

recommended Tabor to a potential student.

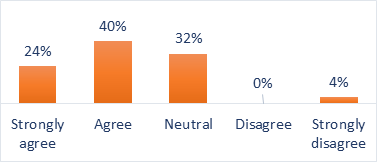

In a 2021 Anabaptist World

editorial, someone wrote, “My education at [another Mennonite college]

was vital in laying a foundation for my life. Professionally and personally,

the ripple effects of my experiences in college are too many to count…I

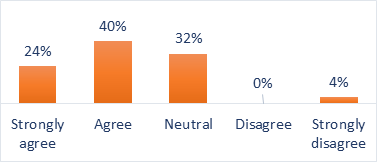

would do it again.” Using a five-point scale from Strongly agree to Strongly

disagree, we asked our classmates about the extent they would agree with

that statement if it referred to Tabor College. Figure 8‑3 summarizes

their responses:

Figure 8‑3 "My education at Tabor was vital… I would do it again.”

Nearly two-thirds agreed or

strongly agreed with that statement. Tabor had played a vital role in

establishing the foundation for the Class of ’67, and if we had to make

that decision over, we’d do it again. About one-third gave a neutral

response—neither particularly positive nor negative. Four percent

strongly disagreed with that statement. We asked everyone to share the

rationale behind their choice.

The responses, perhaps

influenced by how the question was framed, clearly said that Tabor provided “a

strong foundation,” “a good groundwork,” or

“a start for who I was to become.” A number indicated that

Tabor provided a transition from their small-town home communities. One noted, “Given

the limited exposure to the world I received prior to college, Tabor was an

appropriate next step for me.” Another said, “Tabor was a

place for me to understand the narrow scope of the MB world; before that I

thought that was all there was…the main benefit was it helped me to ask

questions.” Someone else described faith formation during college as “not

changing, but growing stronger,” and acknowledged “exploring

the elements of my Christian faith in a way that led to further growth and

understanding later.”

“Life-long

friendships” and meeting a spouse were mentioned by more than a few

as lasting benefits from their years at Tabor.

Some hinted that their academic

training at Tabor was good, but not great. Others praised the academic

preparation for their careers. Several responses mirrored the comment of one

who “found a field of study/work that was the first step toward a

satisfying career.” Similarly, some echoed their response to an

earlier question about a professor who made a life-changing difference by

pointing them in the direction of a career they had not previously considered. Others

reported gaining confidence in themselves, something they had previously

lacked.

Those who were neutral about

Tabor—neither agreeing or not with the statement—said or implied

that they had been shaped more by their previous experience and relationships (e.g.,

“parents and grandparents”) or after (“situations

and experiences after college life”). Some acknowledged that they had

been too immature during their college years to receive the full benefit of

what college had to offer.

Looking back, another noted that

“While I had a great experience, I doubt I would pay today’s

tuition [to attend Tabor].”

back to table of contents

We asked our classmates about

their theological beliefs—and how these had changed over the decades. We

also asked them about their participation in religious activities.

Our data show that we moved toward the two ends of the

theological spectrum. Some became more liberal while others became more

conservative. We were definitely conservative when we arrived at Tabor, but by

the time we left, we were less so. We generally are even less conservative today

as we can see in Figure 9‑1.

Figure

9‑1 Our theological perspectives entering Tabor, leaving Tabor, and

today.

The relative size of the Conservative/Very

Conservative group is the same as it was when we left Tabor, but today, more

of those describe themselves as Very Conservative.

Over the same period, the Liberal/Very Liberal group grew to more than a quarter

of the class. Since we left Tabor, we have moved theologically from the center

toward the two ends of the spectrum, with some becoming more liberal and the

conservatives becoming more conservative.

Given the opportunity to comment

on how their theological perspectives changed since their college years,

classmates who identified themselves as liberals were more inclined to explain

what shaped them. One went so far as to say, “Christianity/spirituality

have been completely left behind, because of the way human beings call

themselves Christians, but don’t live the way they say they

believe.” Others who retain their faith but see it differently than

they once did, spoke of taking the Bible “seriously, but not

literally,” or understanding it to be “metaphorical and not

literal.”

Of those whose views became more

liberal, most attributed the change to relationships with “people from

other religions or faiths” or “a diverse community of

friends and neighbors.” One said that “my children have

stretched my thinking.” More than a few pointed to international

experience, and specifically to teaching and service assignments under MB and

MCC programs; one described their service as having “tremendously

expanded my perspective on who and what Jesus was sent to

‘save.’” Another questioned “the idea that

Christianity is for all. The essence of humanity is kindness, goodness, respect,

and is something that can be found in Buddhists and Muslims, too.”

Those who described themselves

as theologically conservative were less inclined to offer explanatory comments.

Two expressed a similar belief that their Savior or God’s Word “remains

the same yesterday, today, and forever.” One said that “as I

have matured as a Christian, I have become more conservative and biblically

founded.” Others described spiritual changes that didn’t alter

fundamental beliefs, but reported having matured, grown in knowledge of Christ,

and “moved from legalism to grace.” One elaborated by saying

“I am more compassionate and accepting to diverse thinking and

opinions, while not abandoning my core beliefs and values. I am not

confrontational now and more accept[ing] of questioning than I was when I was a

senior at Tabor.”

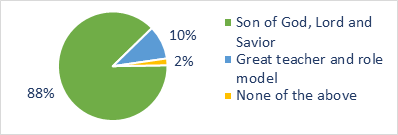

How we view Jesus

We used two questions to learn

more about the underlying assumptions people make about Jesus and the Bible.

A fundamental difference between

Christianity and other religions is how they view Jesus. We gave the

respondents several statements that reflect different views and asked them to

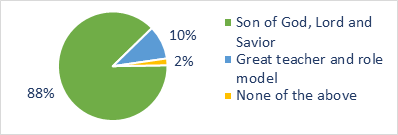

identify the one that most closely aligns with their beliefs. See Figure

9‑2:

Figure

9‑2 Our views of Jesus.

Most of

the Class of ’67 continue to reflect a very evangelical Christian view of

Jesus and his ministry—seeing him as Son

of God, Lord, and Savior. We gave respondents another option: that Jesus

was Simply a prophet and teacher like others of

his time, though better known. None selected it. A national survey in

2020 by LifeWay Research, on the other hand, found that 51% of the people

agreed (or strongly agreed) with the statement saying that Jesus was a great

teacher, but not God. Thirty-six percent disagreed while 12% said they were not

sure.[2]

A 2022 Gallup poll found that the number of people in the

U.S. who believe in God has now dropped to 81%.[3]

As the LifeWay Research study found, however, they just don’t believe

that Jesus is Lord. The Class of ’67 does.

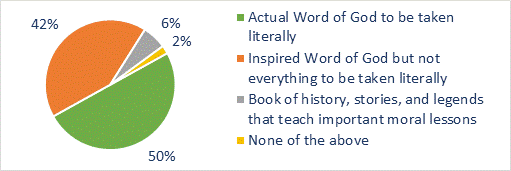

How we view the Bible

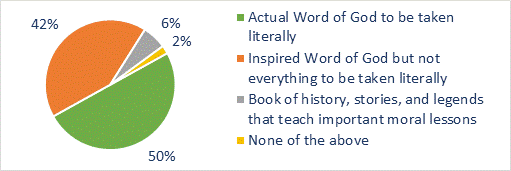

We followed up with a question

about people’s views of the Bible. We asked them to choose a statement

from several options that best described how they see the Bible today. The

responses shown in Figure 9‑3 reflect a conservative view of the Bible.

Figure 9‑3 Our views of the Bible.

The respondents generally held a

conservative view of the Bible but reflected the divisions among many

Christians. Half see the Bible as the Actual Word

of God to be taken literally, word for word. Forty-two percent believe

it is the Inspired Word of God, but not

everything to be taken literally. A few see it as a Book of history, stories, and legends that teach

important moral lessons. As a point of comparison, a recent poll of U.S.

adults found that 20% see the Bible as the “actual word of God.”[4] Forty-nine percent believe it is the

“Inspired word of God” but not necessary the “actual

word of God,” while 29% consider the Bible to be “an ancient

book of fables.”

The data show that

people’s political orientations are reflected in how they view the

Bible. Eighty percent of those in the politically conservative or very

conservative group indicated they see the Bible as The actual Word of God to be taken literally. Twenty

percent of them see the Bible as the Inspired

Word of God but not everything is to be taken literally. Seventy-five

percent of those whose politics place them in the Middle-of-the-road, Liberal, or Very

liberal groups see the Bible as the Inspired

Word of God but not everything is to be taken literally. Five

percent of the politically liberal and middle-of-the-road referred to the Bible

as the Actual World of God to be taken literally,

word for word. Twenty percent of this group called the Bible a book of

history, stories, and legends that teach important moral lessons.

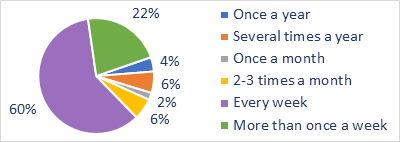

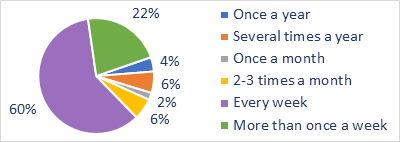

Church attendance might be

considered one objective indicator of religious commitment, so we asked how

often they attended religious services. Because this survey was conducted

during the pandemic when many churches were meeting online only, we asked respondents

how often they attended religious services prior to the pandemic. Figure

9‑4 shows the results:

Figure 9‑4 Attendance at religious services before the pandemic.

A total of 88% indicated that they attended church services

at least two-three times per month. Only 10% said they attended less than once

per month. Although Did not attend religious

services was given as an option, no one selected it.

According to research by the Pew Research Center, 24% of all

Americans attend religious services at least once a week but for adults 65 and

over, that increases to 48%. Sixty-three percent of evangelicals attend weekly.[5] Clearly, the Class of ’67 has

continued to participate in religious services at over twice the rate of the

rest of the U.S. population or their age cohorts.

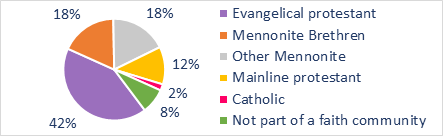

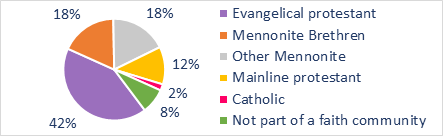

All respondents reported being

part of local churches when they finished high school, so we wanted to know if

this had changed over the years. Figure 9-5

indicates the types of churches of which they were part at the time of this

survey.

Figure 9‑5 Where we worship today.

Though we were overwhelmingly

Mennonite when we came to Tabor, only 36% report worshiping with Mennonite

congregations today. Forty-two percent now say they are part of Evangelical

Protestant congregations.

The fact that 92% of the Class

of ’67 remain part of local congregations today is quite remarkable.

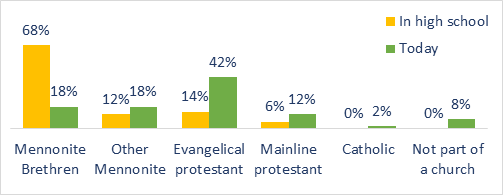

The following graphic shows how

the denominational affiliations of the Class of ’67 changed between 1963,

when most of us were finishing high school, and today:

Figure 9‑6 Change in denominational affiliations between high school and today.

Eighty percent of us were part

of Mennonite churches when we started college. Today, that number has dropped

to 36%, evenly split between Mennonite Brethren

and Other Mennonite. The number of those

who now call themselves Evangelical

Protestant has tripled since 1963. The percentage of those who now

consider themselves Mainline

Protestants has doubled since we started college.

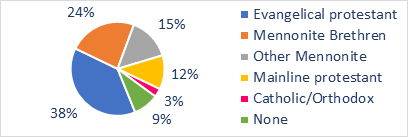

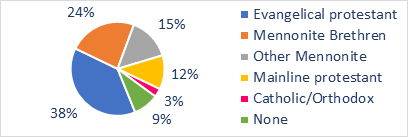

Finding significant movement of

MBs to other denominations, we wondered where they went. The distribution is

shown in Figure 9‑7.

Figure 9‑7 Where those raised MB attend today.

This graph shows where our

classmates who identified themselves as MBs at the start of college ended up. The

destination for MBs was mostly Evangelical

Protestant. It might be argued that today

there is little distinction between Mennonite

Brethren and Evangelical Protestant.

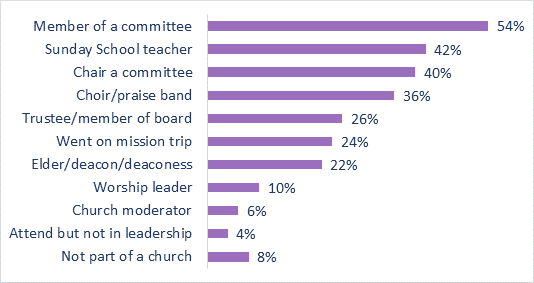

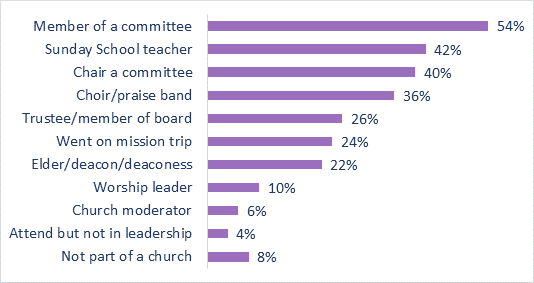

For those who continued to be

part of local congregations, we asked how they had been involved in their

churches. Specifically, we created a list of leadership roles and volunteer

opportunities in church and asked everyone to identify the ways in which they

had served their congregations over the past 15 years. We compiled the results

into Figure 9-8:

Figure 9‑8 Participation in the leadership of our congregations.

Clearly, the church has

continued to be central in the lives of most in our class. Having attended a

Christian college and having remained active in local congregations, it’s

not surprising that they also assumed institutional leadership roles.

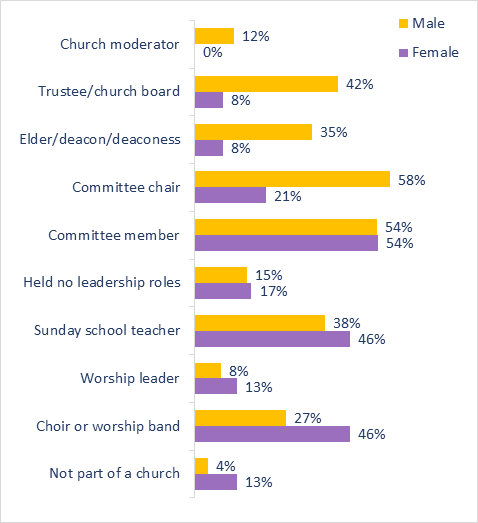

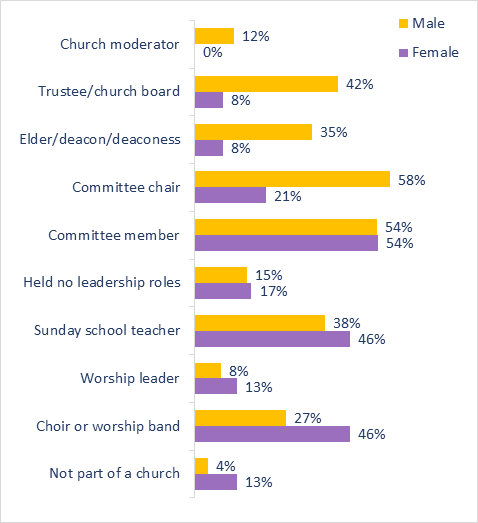

When we broke down leadership

roles and voluntary service by gender (Figure 9-9), an additional story

emerged. Men and women hold dramatically

different roles in their congregations.

Figure 9‑9 Participation in leadership of our congregations by gender.

Women and men were equally

likely to have served on committees, but men were more likely to have chaired them.

Only men had been moderator, and few women served as a trustee or elder/deacon.

The data show that the men in our class have held more

leadership roles in our churches than the women. Likely this is because so many

in our class are now part of evangelical congregations where leadership is

assumed to be the purview of men. It certainly reflects the traditional gender roles

in the MB churches of our youth.

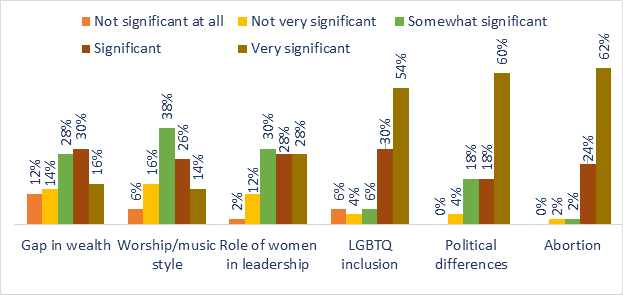

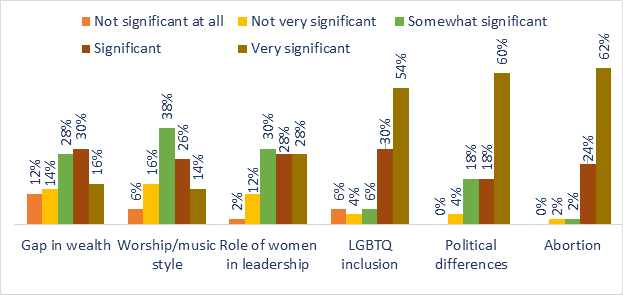

There are many issues straining

the church today. We created a list of issues from our observations and asked

respondents to identify how significant those issues are using a five-point

scale from Not Significant to Very Significant. The question focused on what

they saw as the issues straining the church, writ large, not the

importance or how they personally felt about those issues.

Figure 9‑10 The most significant issues

straining the faith community today.

The hot-button issues are clear:

abortion, political differences, and the inclusion of LGBTQ congregants in

church. (Note that these results pre-date the June 2022 Supreme Court decision

on abortion.) The role of women in leadership causes less strain than these

three but is more important than differences in worship/music styles and gaps

in personal wealth.

back to table of contents

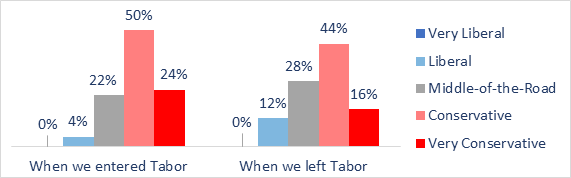

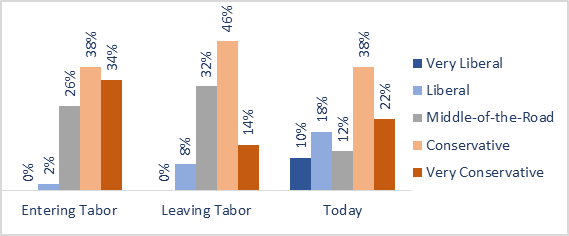

With politics emerging as a

significant issue in society, we asked our respondents about their political

perspectives and their involvement in the political process.

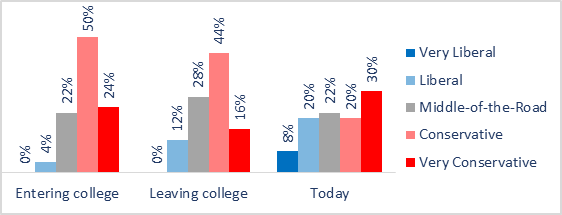

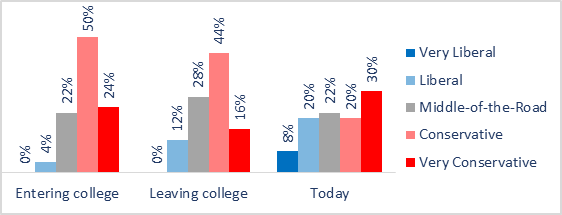

As we did with theological

perspectives, we asked our classmates about political perspectives: when we arrived

at Tabor, when we left Tabor, and today. The following graphic shows what we

heard:

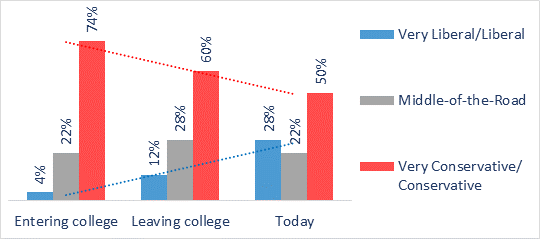

Figure 10‑1 Political perspectives entering

Tabor, leaving Tabor, and today.

Entering college, very few considered themselves politically

Liberal; none said they were Very Liberal. However, by the time

we left college, those calling themselves Liberal

had tripled. The percentage of those who considered themselves Conservative decreased during college as did the

Very Conservative group.

The greater change—in both directions—took place

after college. The number who now call themselves liberal has more than

doubled. On the other side of the political spectrum, there was also a significant

shift, from Conservative to Very Conservative.

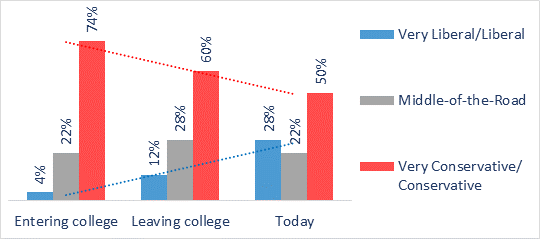

In order to visualize the trends, we reduced the

political spectrum from five points to three—collapsing Very liberal/Liberal into one

group and Very conservative/Conservative into

another in Figure 10‑2.

Figure 10‑2 Trends in our political perspectives.

This revealed a gradual, but significant, evolution in

our class’s political profile. The combined Liberal category tripled from

before college to after college. It subsequently more than doubled to

the present. The combined Conservative group dropped during our

college years, and since that time, it has decreased further to

today.

Based on this graphic, it’s clear that our

class has realigned itself into a new distribution across

the political spectrum.

With more to learn in these data, we will be exploring this

further.

We found something very

interesting when we asked people to comment on the change in their political

perspectives. Those identifying themselves as Liberal

or Middle-of-the-Road were more inclined

to discuss their change and the reasons for it, than those on the conservative

side of the spectrum. Those who had become more liberal attributed their new

perspectives to a greater awareness of poverty, injustice, and the inequitable

distribution of wealth. They identified reading, discussion, small-group

studies, and “more exposure to the world” as sources of that

awareness. As with the theological-perspective question, some referred to “working

overseas” and to “exposure to varied social, economic, and

cultural conditions during travel” as particularly formative.

Several characterized their

liberal tendencies as “Trying to be a Jesus follower in the real world,”

or similarly: “I have become more liberal and more socially minded. I

believe that Jesus was this kind of person who cared for the whole person.”

Two, who now position themselves

as middle-of-the-road, asserted, in the

words of one, “Donald Trump soured me on conservative [political] positions.”

The predominant theme among those

identifying themselves as politically conservative was that the nation had

drifted away from them. Another phrased the same idea another way: “Still

conservative. Somebody’s moved the middle.” And another: “As

I see the world around me getting more and more liberal, with all the hatred

and anger, I have moved to be more conservative.” One asserted that “I

became more conservative as I got older and the world got more liberal.” Another

lamented “watching the US drift from a constitutional republic toward

being a welfare state.”

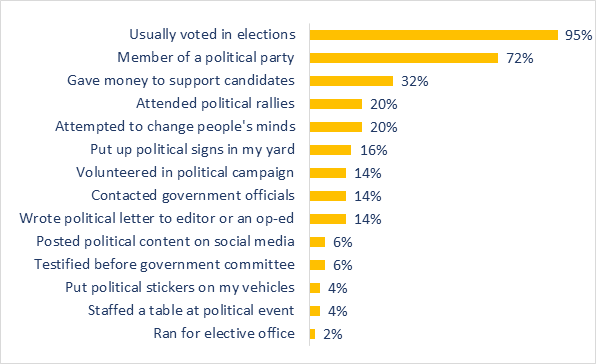

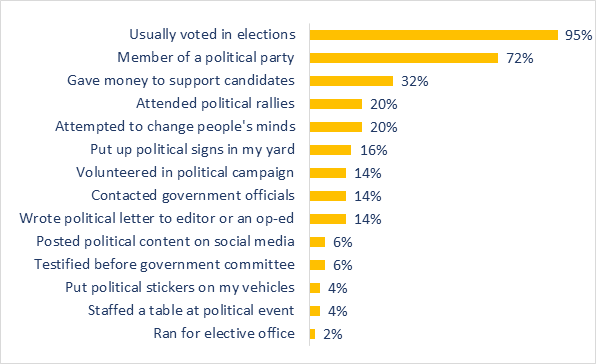

We not only asked people about

their political beliefs—where they stood on a continuum from left to

right—but we also about their political involvement. We provided a list

of political actions and asked everyone to indicate the ones in which they had

participated. The compilation is shown in Figure 10‑3.

Figure 10‑3 Ways in which we have been engaged politically.

Although only one person among our respondents ever ran for

elective office, we know that two of our classmates, now deceased, had served

in their respective state legislatures.

Impressively, 95% usually voted, far

exceeding the national average. By comparison, in the 2020 U.S. election which

had the highest voter turnout in the 21st century, 67% of the

eligible voters actually voted; even among adults 65-74 and adults 75 and

older, the number was only 71%.[6]

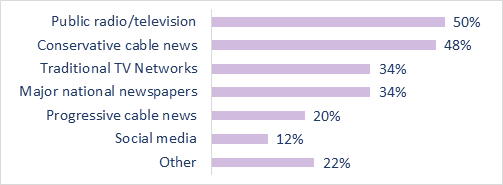

Sources of national and international news

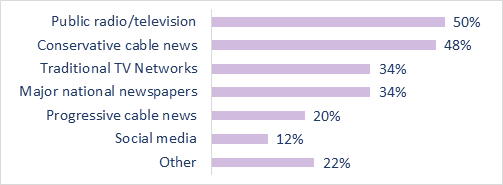

We know that people get their

news about the nation and the world from different sources. News sources tend

to have a perspective, so we asked our classmates to identify their three most

trusted sources for national and international news. The following graphic

shows what we learned:

Figure 10‑4 The types of sources of national and

international news that we trust.

Like the country at large, our classmates have widely varied

preferences for the news sources they trust. Given the chance to identify three

different types of sources, no single type was favored by more than half of the

respondents. Two distinctly different types of sources—public

radio and television, and conservative cable news—were each trusted by

about half of the respondents. Traditional TV networks and major national

newspapers each were mentioned by about one in three; progressive cable news by

one in five; and social media by one in eight. Significantly, although we did

list not Christian radio as an option, 22% of the class wrote it in as one of

their three most trusted sources of news.

back to table of contents

We wanted to learn more about

our classmates’ engagement with civil society, the network of voluntary/non-governmental

organizations that are formed to address problems in their communities and the

world. We asked people to identify the types of voluntary organizations in

which they were involved. Since they had already responded to questions about

their participation in their local congregations, we asked about their

participation in non-church organizations as well.

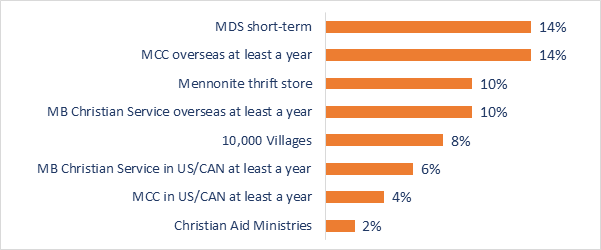

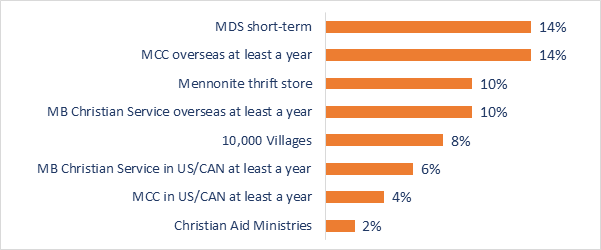

As we noted earlier, 80% of our

class had Mennonite roots, so we asked how many of them had served with one of

the Mennonite service organizations. We presented a range of service

opportunities from those lasting a few days to a few years. Tabor actively

encouraged MB Christian Service overseas.

Thirty-eight percent of our class volunteered short-term with

at least one Mennonite social service organization. Figure 11‑1 shows the

percentages that served in each of the following organizations:

Figure

11‑1 Our service with Mennonite organizations.

Twenty-four percent of our class

served at least a year with the Mennonite Central Committee and/or the

Mennonite Brethren Christian Service Program. Both MCC and MB Christian Service

assignments fulfilled the selective service requirements for men. Twenty-four

percent of our classmates volunteered with at least one short-term Mennonite

organization.

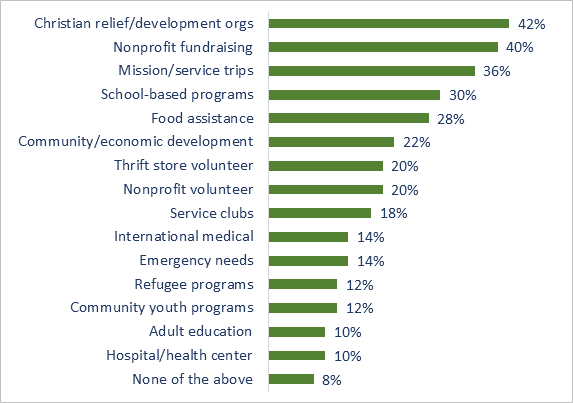

We were also interested in the extent to which our class was

involved in voluntarism outside their local congregations and outside Mennonite

service organizations. We listed the types of organizations with which people

typically volunteer and asked everyone to identify all the ones in which they had

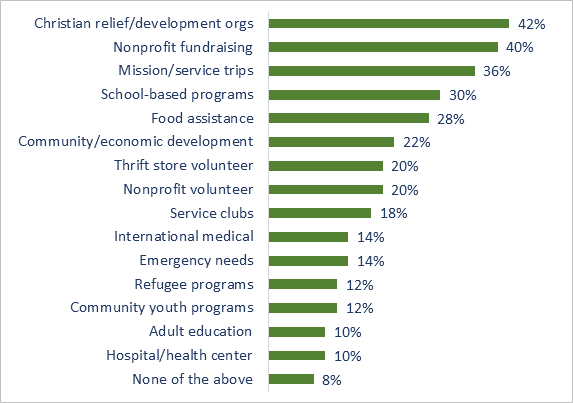

been involved. Figure 11‑2 shows what we found:

Figure 11‑2 Our volunteer participation in

different types of organizations outside our local congregation.

Ninety-two percent volunteered

with at least one of these types of organizations. Most identified multiple

organizations. Christian organizations involved in relief and development were

identified most often. We know anecdotally that people in our study have

volunteered with the Samaritan’s Purse “Shoe Box” program,

MCC relief sales, World Vision program activities, etc. The question about

mission/service trips specifically excluded mission trips sponsored by

people’s own churches. Thirty percent volunteered with school programs

and a similar number in food assistance programs such as Head Start and local

food banks.

While our classmates held

leadership roles in their churches, they were also serving with community and

other nonprofit organizations. They are actively engaged in of civil society.

Donating money is another element of voluntarism, so we asked

everyone to indicate which types of organizations they support financially. See

Figure 11‑3:

Figure 11‑3 Organizations through which we do

our charitable giving.

Most of our classmates give to

their churches/faith communities. Just under half support other religious

nonprofit organizations, social service organizations, and educational

institutions. Social justice organizations, advocacy groups, and political

groups are much lower priorities.

Our class is quite charitable when compared to the rest of

the American population. They not only support their churches but also other

nonprofit organizations and groups addressing the needs of society. A Gallup

Poll in 2020 found that 73% of Americans donated to charity during the previous

year, although that is a drop of 6% since 2009.[7]

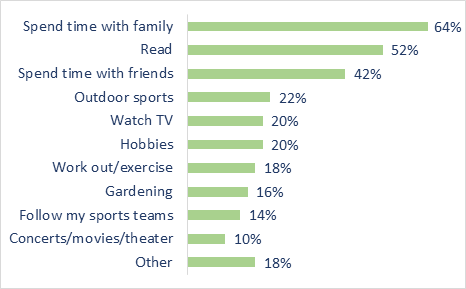

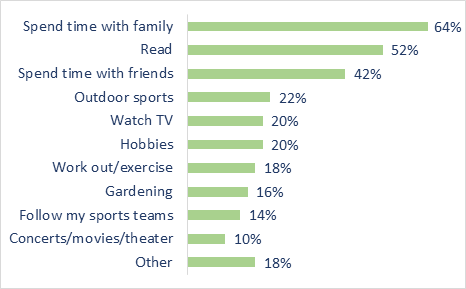

We identified a list of leisure

time activities in which people like us are typically involved and then asked

everyone to select the three they value the most. Figure 11‑4 shows the

results:

Figure 11‑4 The top ways in which we spend our

free time.

We enjoy spending our leisure

time with family, reading, and friends. We are social creatures. Two of the

three clearly favored leisure-time activities involved spending time with

family and friends. Beyond that, we enjoy a wide range of equally ranked

individual activities.

back to table of contents

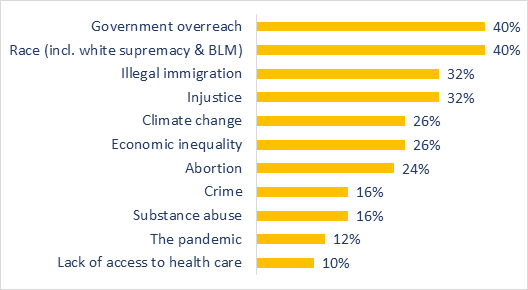

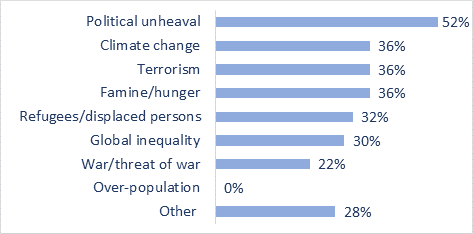

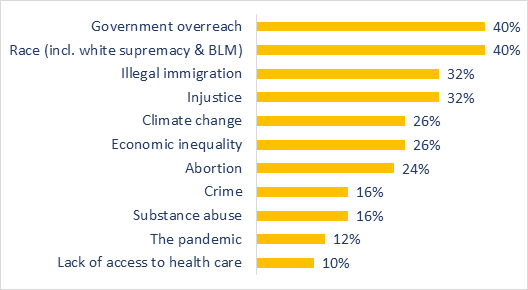

We identified a list of issues facing the nation today.

Then we asked everyone to select the three issues they felt were the most

important. As a point of reference, all but one of those responding to our

survey currently live in the United States. The following figure shows what our

classmates see as their top three issues:

Figure 12‑1 What we see as the most important issues facing our nation.

Government

overreach and Race were two of those

issues considered most significant. One third identified Illegal immigration and Injustice as critical issues.

We gave Other as an option and invited comment. Five of

the eight comments addressed spiritual issues: “spiritual ignorance,”

“postmodern acceptance of no absolutes for truth,” “the

church being ineffective,” and “failure in the spiritual

life of believers.”

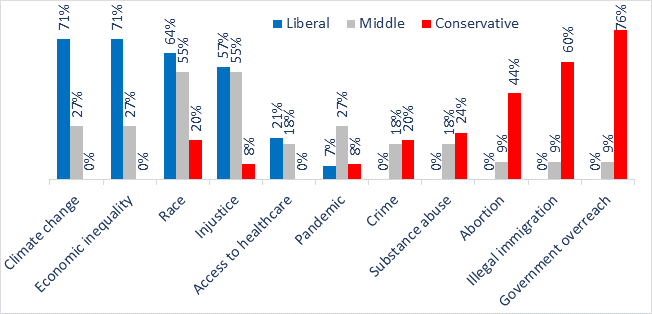

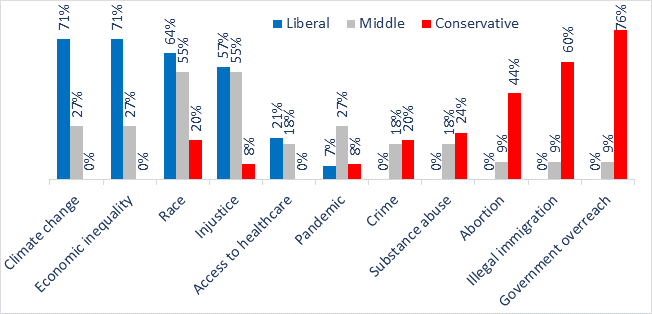

We wondered if political differences accounted for what

people identified as the most critical issues facing the nation. We again

used the three-level, political scale we had created earlier (Liberal,

Middle-of-the-road, and Conservative). Figure 12-2 clearly shows that political

views matter when it comes to identifying what people see as the most important

issues facing the nation.

Figure 12‑2 Our political perspectives and the

most important issues facing the nation. (Each respondent could select up to

three.)

Political conservatives (the red

bars) identified Government Overreach, Illegal Immigration, and Abortion as the most important issues facing the

nation. None of the liberals did. (It is important to note that this survey carried

out well before the 2022 Supreme Court decision placed abortion front and

center in national discussions. Were this survey to be conducted later in 2022,

the responses would probably be quite different.)

Liberals (the blue bars)

identified Climate Change, Economic Inequality, Race, and Injustice

as primary issues. Only a few conservatives included Race or Injustice

as a top concern.

Those in the political center (the

gray bars) aligned themselves more closely with the liberals than the

conservatives, identifying Race and Injustice as significant issues followed by Climate change, Inequality,

and The pandemic.

We found no significant

differences between the views of men and women.

The most important finding here

is that we have two groups who almost completely disagree with each other about

the critical issues facing the nation. Liberals and moderates largely agreed on

their top issues. As a group, conservatives largely agreed among themselves on

a separate set of issues, with essentially no overlap with the rest of the

class. The only overlap was on Race but

it’s not clear from the data if they were concerned about it for the same

reasons.

This fundamental difference on

how we define the nation's most pressing problems clearly mirrors what we are

seeing in our nation today.

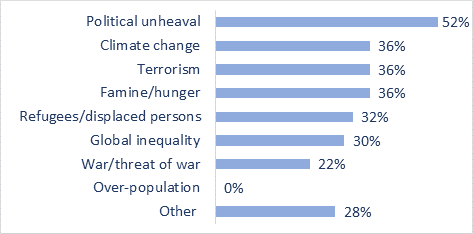

We asked everyone to look at a set of issues facing the

world today and to identify the three they considered the most important. (We note

that the survey was taken before the Russian build-up and attack on Ukraine.) Figure

12‑3 shows what we heard:

Figure

12‑3 The most important issues facing our world. (Each respondent

could select up to three.)

More than half identified Political upheaval as one of the top three

issues facing the world. Interestingly, no one identified Over-population, a major concern in the 1970s,

as a top concern today.

Most of the remaining options were

selected by between 22% and 36% of the class. We found little difference

between how men and women saw these issues. People’s differing political

views were reflected in what they identified as the most significant world

issues, but the differences were not as dramatic as we found when we asked

about national issues.

While the majority of our class did

identify three national and world issues, there was one notable exception. Most

of those who identified themselves as Very

Conservative used only half of their selections.

We included an Other category and gave people an opportunity to

propose something not on the list. One theme arose repeatedly: Ten of the 14 comments

identified the major problems facing the world in spiritual terms such as,

“world without Jesus,” “fear of God,” “exposure

to the Word of God,” “lack of God awareness,” and

“removal of Christianity from daily life.”

Given the differences in our

classmates’ theological views and differences in their political views,

we looked at how the two aligned on a scale from Very

Conservative to Very Liberal. Table

12‑1 compares the two:

Table 12‑1 The relationship between our

theological and political perspectives.

|

Political Perspectives

|

|

Liberal

|

Middle- of-the- Road

|

Conservative

|

|

Theological Perspectives

|

Conservative

|

2%

|

10%

|

48%

|

|

Middle-of-the-Road

|

|

10%

|

2%

|

|

Liberal

|

26%

|

2%

|

|

Twenty-six percent of the class

consider themselves Liberal

or Very Liberal in both

politics and theology. Ten percent identify themselves as Middle-of-the-road in both politics and

theology. Forty-eight percent are Conservative

or Very Conservative in both

politics and theology. This means that when we define ourselves on a spectrum

from liberal to conservative, for 84%, our politics and theology essentially

overlay. Only 16% of the class hold political and theological views that

don’t closely align.

We performed additional

statistical analyses on the strength of the relationship between theological

and political perspectives. We found that the correlation between the two became

stronger over time—from starting college, to completing college, to

now. Our political views and theological views align more closely over

time, and the number of outliers decreases. We will be exploring this further

in future studies.

back to table of contents

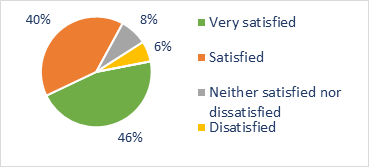

Life has its ups and downs,

challenges and rewards. We also wanted to know how people feel about their

lives when they look back. Social scientists sometimes frame this in terms of

satisfaction and happiness. Satisfaction is what people feel

when they look back at the trajectory of their lives. Happiness refers

to how things are going these days.

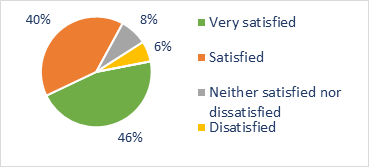

Figure 13‑1 shows what we

learned when we asked our classmates about how satisfied they are with their

lives.

Figure

13‑1 Satisfaction with life.

Eighty-six percent said that

they were Satisfied or Very Satisfied with their lives.

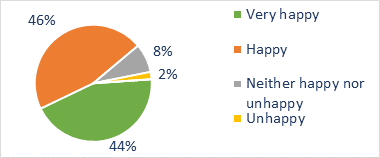

We asked our respondents to

reflect further. With everything taken together, we asked “how happy are

you these days?”

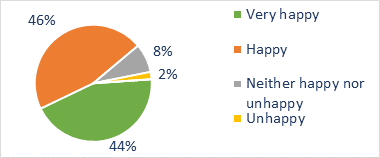

Figure

13‑2 Happiness in life.

Ninety percent said they were Happy or Very Happy

these days; only one person selected Unhappy.

It is interesting to compare these reports of overall

happiness and satisfaction with Figure

7‑4 that measured people's assessment of the meaningfulness of their

careers. In all three cases the combination of classmates who found their

careers meaningful/very meaningful and

their assessments of their lives overall satisfied/very

satisfied and happy/very happy were

in the 85-92% range.

A Gallup poll in early 2022 found that Americans felt very

satisfied with their lives in spite of however they felt about things in the

US. Ninety-two percent of those who attend church services regularly are

satisfied with their lives, compared to 82% of those who attend services less

than monthly.[8]

Our classmates match up well with those church-goers.

When we asked these two questions, the results were nearly

identical. Almost everyone was satisfied with the way their lives had gone

overall and characterized themselves as happy at present.

In an earlier question we asked for people's assessment of

the meaningfulness of their careers. The results there, as reported in Figure

7‑4, were strikingly similar. In all three cases the combination of

classmates who found their careers meaningful/very meaningful and their

assessments of their lives overall satisfied/very satisfied and currently

happy/very happy were in the 85-92% range.

Clearly, these highly positive results should not be taken

as an indication that all was smooth sailing and free of crises for our

classmates. It would take another research project to understand how to account

for such uniformly favorable self-assessments. In any event, it appears that

for most, life has been good.

back to table of contents

Sixty years ago, those of us who

became the Tabor Class of ‘67 were anticipating our senior year of high

school during which we would complete our college applications and decide where

to enroll. This document reports the results of a survey of those of us who

chose Tabor. It examined the backgrounds from which we came and summarized our

personal reflections about our lives at three points in time over the past 60

years: when we arrived at Tabor, when we graduated (or left) Tabor, and today.

We mostly came from highly religious, rural communities;

only one in this study came from outside North America. All but a few lived on

farms or small towns and attended small high schools. Many came from families

where neither parent had graduated from high school. We were raised in

Mennonite Brethren (MB) churches and reflected the conservative theological and

political perspectives of these congregations.

We chose Tabor primarily because of the influence of those

around us. Tabor was an MB college, and we knew people who had attended there.

Our families and home communities believed education was important and

encouraged us to enroll in college. Though some of our parents had little

formal education, this was not a barrier to our own educational achievement.

Nor was coming from small high schools or families with limited financial

means.

Participants in our study referred to Tabor as a broadening

experience. It opened our minds and introduced us to new ideas, perspectives,

and people that extended far beyond the small communities in which we were